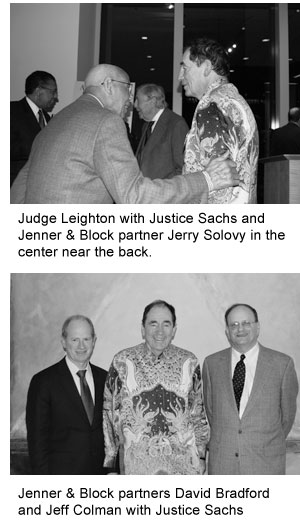

Editor’s Note: On February 2, 2010, Justice Albie Sachs spoke at Jenner & Block in Chicago about his lifetime of opposition to Apartheid and his new book, The Strange Alchemy of Life and Law. The following summary is taken from the introduction of Justice Sachs by Jenner & Block Partner Jeff Colman.

Editor’s Note: On February 2, 2010, Justice Albie Sachs spoke at Jenner & Block in Chicago about his lifetime of opposition to Apartheid and his new book, The Strange Alchemy of Life and Law. The following summary is taken from the introduction of Justice Sachs by Jenner & Block Partner Jeff Colman.

Justice Albie Sachs is one of the most heroic lawyers and judges of the 20th and 21st centuries. Sixty years ago, Albie Sachs had already embarked upon a lifetime of opposition to Apartheid and devotion to the struggle for equality in his nation. At age 6, Albie’s father gave him a card expressing the wish that Albie grow up to be a soldier in the fight for liberation. By age 17, he was actively opposing the repressive laws of South Africa. As a 21-year-old lawyer, he represented the opponents of Apartheid and became himself a victim of the brutal regime in South Africa: imprisoned on two occasions; put in solitary confinement—once for 168 days and once for 90 days; tortured through sleep deprivation and other brutalities; exiled for almost 24 years (1966-1990) in England and Mozambique—living, as he describes it, as “a lawyer and an outlaw,” and, in 1988, South African secret police bombed his car, causing him extraordinary injuries including the loss of an arm and the sight in one eye. For all those years, he was speaking out against Apartheid and representing the opponents of that regime.

As Apartheid was finally coming to its end, Albie Sachs returned to South Africa and was asked to help draft the Constitution of the new Republic of South Africa and to help create a democratic government in a land where no democratic principles existed. In 1994, Nelson Mandela appointed him to the Constitutional Court of South Africa where he served with great distinction for 15 years, retiring just a few months ago. On the Constitutional Court, Justice Sachs participated in some of the most momentous decisions of any court in the world: declaring the death penalty unconstitutional; declaring unconstitutional the definition of marriage as being exclusively between a man and a woman; speaking to the constitutional duty to provide effective remedies against domestic violence; addressing discrimination against HIV-positive persons and discrimination in a wide variety of other areas; and, declaring constitutional rights in the areas of housing, healthcare, and the ability to obtain basic public services.

Newsweek’s Dahlia Lithwick recently published an opinion piece entitled “The View from the Bench” that provides some insight into Justice Sachs’ book. She writes very eloquently about what she calls two legal “swan songs”: Justice Stevens’ dissent in the recent campaign finance decision—Citizens United v. FEC; and Justice Sachs’ new book, The Strange Alchemy of Life and Law. In his introductory comments, Mr. Colman stated it was his assumption that Justice Stevens and Justice Sachs would both state unequivocally that Ms. Lithwick is wrong about one thing—these are not “swan songs.” Justice Stevens has many more songs to sing this judicial term and thereafter. In operatic terms, Justice Sachs’ book may be a great aria but clearly no “swan song.” Mr. Colman further observed that Justice Stevens and Justice Sachs have many more things in common: lifetime of devotion to the rule of law, to integrity, to decency and professionalism; unparalleled devotion to the principles of equal protection of the law—to protecting the rights of the most oppressed and disenfranchised among us; and, they also now have Jenner & Block in common—we’re graced by Justice Sachs’ appearance here, as we were by John Paul Stevens’ presence as an associate at this law firm 60 years ago.

Justice Sachs’ book is about his personal life and the impact it has had on his decision-making as a judge. As he writes, “If law is a machine, we are the ghosts that inhabit it and give it life.” Ms. Lithwick further described Albie Sachs’ book in Newsweek in the following words:

It is impossible to imagine a justice of the United States Supreme Court sitting down to pen a memoir like Sachs.’ It would mean acknowledging that judges are not made of microchips, and that doing justice means more than just calling balls and strikes (in the favored formulation of our day). If an American judge described, as Sachs does, a party to an appeal “lying on the bare field at night staring up at the stars as the rain clouds gathered and asking: why are we born to live like this, why must my children grow up without a home?” we would urge swift impeachment, accompanied by pharmacological intervention. ■