ISBA Members, please login to join this section

Illinois Supreme Court Decision in People v. Wells: ‘A Deal’s a Deal’

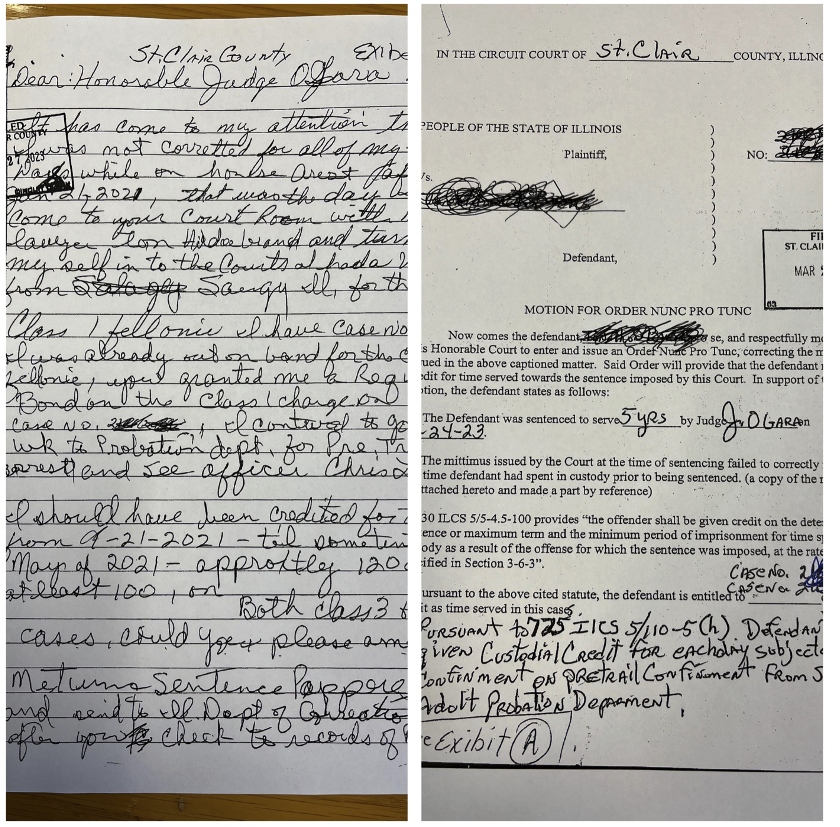

A familiar sight to practitioners and judges in the felony courts is a letter /pleading sent by a person who is incarcerated in the Illinois Department of Corrections seeking to receive more credit for time or credits earned before the plea and or sentencing.

Look Familiar? Well, the Illinois Supreme Court decided People v. Wells, 2024 IL 129402, on March 21, 2024 which is very instructive on handling this situation, and helpful in guiding practitioners and courts of how to insure proper sentence credit for the accused.

The defendant Emmanuel Wells entered into a fully negotiated plea agreement including a plea to one count of unlawful possession of cannabis with the intent to deliver, the state dismissing the remaining counts, a minimum sentence of six years in the IDOC, defendant pays a $100,000 street value fine and

Mr. Wells receives 54 days credit for time served in custody towards the six year sentence.

Mr. Wells served 54 days in jail but was released on a 24-hour GPS monitoring with ankle bracelet. He had a curfew and was initially only allowed to go out of his home for work, church and medical appointments. He was eventually allowed an extended curfew until the GPS conditions were removed after almost seven months.

When he pled guilty pursuant to a fully negotiated disposition, Mr. Wells confirmed the agreement for 54 days credit with the court and signed a written plea agreement as well. He did not file a postplea motion or direct appeal, but instead filed a motion titled (you guessed it), a motion for order nunc pro tunc requesting credit for the time on “GPS Monitoring.” The trial court denied the motion, and he appealed. The denial was affirmed by the Fourth District Appellate Court and then the Illinois Supreme Court granted a petition for leave to appeal.

The court first looked at how Mr. Wells labeled his request for additional credit by not filing a motion under Illinois Supreme Court Rule 472. The Rule states that in criminal cases, the circuit court retains jurisdiction to correct sentencing errors at any time following judgment and after notice to the parties, and, in section (3), includes errors in the calculation of presentence custody credit. Because the motion to correct his mittimus and sentence was to “reflect credit that he believed he was entitled to, the motion is consistent with the Rule’s remedy he did not forfeit a claim under Rule 472(a)(3). People v. Wells, 2024 IL 129402 ¶ 16. Quoting People v. Patrick, 2011 IL 111666 ¶ 34, the decision noted “Generally, the character of a motion is determined by its content or substance, not by the label placed on it by the movant.”

An initial takeaway lesson is that requests from defendants or arguably their counsel, are not so easily dismissed by their label, but rather further inquiry may be warranted. Shakespeare’s line in Romeo and Juliet , Act II, Scene II is brought to mind, “What’s in a name. That which we call a rose, By any other word would smell as sweet.”

Indeed, going beyond the claim of waiver of remedy under Rule 472, the state conceded that aside from the plea agreement, Mr. Wells was arguably entitled to 81 days credit on the GPS monitor served before less restrctive conditions were imposed (an additional 27 days credit beyond the plea agreement). But, that was not the agreement and the state “steadfastly rejected Wells claim to the credit not included in the agreement” Wells at ¶26. The Illinois Supreme Court ultimately turned to “the dispositive issue on Wells claim for credit is whether Wells, by entering into a fully negotiated guilty plea that granted him 54 days of credit, agreed to forgo his right to credit for the time he spent on home detention.” Wells at ¶19.

The court noted the long standing proposition that plea agreements are governed to some extent by contract law principles of exchanged promises to perform or refrain from performing specified actions. People v. Evans, 174 Ill. 2d 320, 327(1996). The Wells decision noted that there arises a presumption that in a fully negociated plea agreement that imports on its face to be the complete expression of the whole agreement that the parties “introduced into it every material item and term, and parole evidence cannot be admitted to add another term to the agreement although the writing contains nothing (about the additional credit thet he arguably should receive). Wells at ¶ 21-22.

The Wells decision looked to the “four corners” rule of contract interpretation. The language of the contract and that neither party should be able to unilaterally renege or seek modification due to an uninduced mistake, a change of mind. Evans, 174 Ill. 2d at 317. Noting People v. Whitfield, 217 Ill.2d 177, 190 (2005), when a defendant enters into a fully negotiated plea agreement for the exchange of dismissal of counts, a certain sentence recommendation”both the state and the defendant must be bound by the terms of the agreement.”

Based on all of these principles, the court held that “where a fully negotiated plea deal represents a complete and final expression of the parties’ agreement, a presumption arises that every material right and obligation is included and neither party may unilaterally seek modification of the agreement.” ¶ 24.

The court also noted that contract principles in plea agreements are tempered in some instances by due process concerns, but here, such concerns were not raised .While Wells situation may not have been a typical waiver, an “intentional relinquishment of a known right,” and it may not be clear that Wells was fully aware or his right to statutory credit for additional GPS time, the court found that Wells “waived the right to statutory credit by entering into a fully negotiated plea and that he is “forclosed from now modifying the credit term of the agreement” Wells at ¶ 25.

What about it being an oversight? Maybe the parties were mutually mistaken about the credit? The Wells decision addresses this possibility by noting that the “mutual mistake may be rectified by recourse to contract reformation, where they are in actual agreement, and their true intent may be discerned” ¶ 26. But, alas, this was not the case for Mr. Wells. Again, the state rejected the claim for more than 54 days credit and there was no “mutual mistake.”

What about an “uninduced mistake “ on Mr. Wells behalf? He can’t unilaterally seek to modify the terms of the agreement, but instead must seek to move to withdraw or invalidate his guilty plea. “He (instead) seeks to maintain the benefits of the plea agreement, the dismissal of charges and minumum sentence, while increasing the amount of credit he receives.” Wells at ¶27. He did not timely seek to withdraw his guilty plea and his claim to additional credit is finished.

This decision also “overruled” People v. Ford, 2020 IL App (2d) 200252 and People v. Malone, 2023 IL App (3d)210612 ¶ 19 to the extent that those cases were inconsistent with Wells. ¶28.

In Ford and Malone, both decisions noted that the record did not conclusively show that the parties agreed to exclude credit, and that the circuit court should not have denied the Rule 472 motions to amend the sentencing mitimus to reflect the credit. The Wells decision flatly states, “Contrary to these cases, the presumption runs in favor of enforcing the specific terms of a plea deal that is a complete and final expression of the parties agreement.” Wells at ¶28. (Emphasis added).

So, what does this mean when we receive the letters/motions-however they are titled?And better yet, how can we adjust plea practices to make sure that all credits are fully accounted for in the plea?

As an initial matter, a written plea agreement – or a mittimus which has been reviewed by defense counsel and the defendant -should be acknowledged on the record by all the parties and the defendant. The circuit court ought to confirm the terms and the specific days of credit on the record with the defendant. If the defendant has been on GPS, home confinement or has attended classes, counseling or other additional new statutory credits which now apply, the court might want to inquire of defense counsel and the state to ascertain if the plea agreement is meant to incorporate some or all dates and activities. And if not, that would be clearly on the record, in the sentencing mittimus or a written plea agreement if one is used.

Defense counsel needs to be attuned to all the credits that the client is entitled to in entering into plea negotiations. Likewise, the prosecution needs to be aware of the credits that may accrue and whether they wish to agree to credits in light of any other sentencing concessions that they are binding the state to in reaching the agreement.

What about that letter/motion we receive? Wells seems to be clear that unless the parties can agree that a “contract reformation” is in order, and that an amended mittimus can be entered to give the defendant additional credit that was missed, the motion is doomed. This is predicated, of course, on whether enough attention was given to those pesky credit details at the time of the guilty plea. Often, in the author’s experience, when we have received this letter, the parties and the court confer and an amended sentencing mittimus is issued ultimately resolving the problem. That was the case on the letter/motion included with this article. If the parties don’t agree though, the Wells decision clearly answers the question by firmly holding that “a deal’s a deal.”